I recently sent this as email to a colleague. You’ll be glad to know we sorted things out :0)

—

The little chat we had last week about AngularJS has been playing on my mind. As you know I’m not against JavaScript (I love it, and have even written an Open Source JavaScript library) and I have a personal project partly planned to try out AngularJS, which looks awesome.

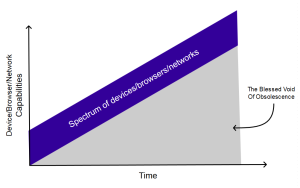

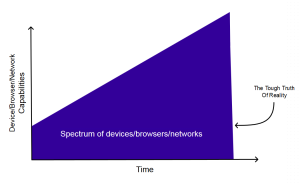

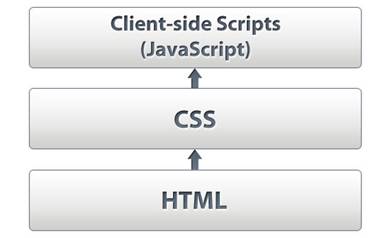

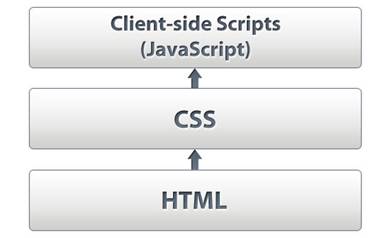

However, your comment that “progressive enhancement is one way to do it” (emphasis mine) bothers me. A lot. I’ve heard this attitude from a lot of developers, and I believe it’s wrong. Not because I believe every website or app (more on the difference between those two things later) should never use JavaScript, but because it ignores the fundamental layers of the web which cry out for a progressive enhancement approach. These layers are:

Here’s how a browser works (more detail).

- It requests a URL and receives an HTML document

- It parses that document and finds the assets it needs to download: images and other media, CSS, JavaScript

- It downloads these assets (there are rules and constraints about how this happens which vary slightly from browser to browser, but here’s the basics):

- CSS files get downloaded and parsed generally very quickly, meaning the page is styled

- JavaScript files get downloaded one-by-one, parsed then executed in turn

- Images and other media files are downloaded

Let’s look at the absolute fundamental layer: the HTML document.

HTML

Way back in the beginning of the web there was only the HTML document on a web page; no CSS, no JavaScript (very early HTML didn’t even have images). In fact without HTML there is no web page at all: it’s the purpose of HTML to make a web page real. And a set of URLs, for example the URLs under a domain like my-site.com, which doesn’t return at least one HTML document is arguably not a website.

Yes, URLs can also be used to download other resources such as images, PDF files, videos etc. But a website is a website because it serves HTML documents, even if those document just act as indexes of the URLs of other (types of) resources.

HTML is the fundamental building block of the web, and software which can’t parse and render HTML (we’ve not even got to CSS or JavaScript yet) can’t call itself a web browser. That would be like software which can’t open a .txt file calling itself a text editor, or software which doesn’t understand .jpg files calling itself an image editor. So we have software – web browsers – which use URLs to parse and render HTML. That is the fundamental, non-negotiable, base layer of a web page, and therefore the web.

One of the great things about all HTML parsing engines is they are very forgiving about the HTML they read. If you make a mistake in the HTML (leave out a closing tag, whatever) they will do their best to render the entire page anyway. It’s not like XML where one mistake will make the whole document invalid. In fact that’s one of the main reasons why XHTML lost in favour of the looser HTML5 standard – because when XHTML was served with its proper MIME type a single syntax mistake would make the page invalid.

And if a web browser encounters elements or attributes it doesn’t recognise it will just carry on. This is the basis on which Web Components are built.

So even serving a broken HTML page, or one with unknown elements or attributes, will probably result in a readable document.

CSS

The next layer is CSS. At this point we’ve left the fundamentals and are onto optional components. That’s right – for a working web page CSS is optional! The page might not *look* very nice, but a well-structured page of HTML will be entirely usable even with no styling, in the same way that water is entirely drinkable without any flavourings.

But most – but not every – browser supports CSS (the basics of it, at least), so why do I treat it as optional? There are a few reasons. Firstly CSS might be turned off (which is very unlikely, but possible). But more importantly the CSS file might not be available or parsable:

- The server hosting the CSS file may be offline

- The file may be temporarily unreadable

- The URL for the file may be wrong

- DNS settings may be incorrect

- The CDN may be down

- The file may be empty

- The file contains something that isn’t CSS or a syntax error

There may be lots of other problems, I’m sure you can think of some.

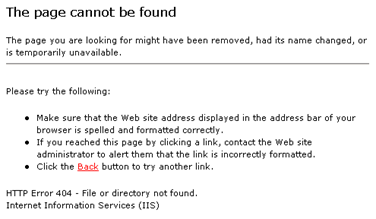

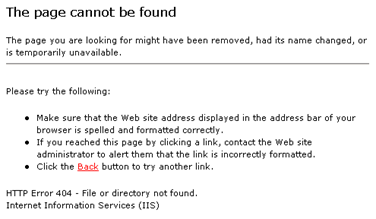

Now, any one of those errors could also be a problem with an HTML document. In fact if the document is being served from a CMS then there are a lot more things that could go wrong. But if any of those errors happen for an HTML document then the browser doesn’t have a web page to parse and render at all. Browsers have mechanisms to handle that, because everyone knows that URLs change all the time (even if they shouldn’t):

So CSS is optional; it is layered on top of the fundamental layer (HTML) to provide additional benefits to the user – a nicely styled page.

And in the same way that web browsers are forgiving about the HTML they parse, they are also forgiving about CSS. You can serve a CSS file with syntax errors and the parts the rendering engine *can* parse correctly it will, and will ignore the rest.

So if an HTML document links to a CSS file which contains partially broken syntax the page will still be partially styled.

JavaScript

Now we come to the top layer, the client-side script.

I don’t need to tell you that JavaScript is sexy at the moment, and rightly so – it is a powerful and fun language. And the fact it’s built into every modern web browser arguably gives it a reach far wider than any other development platform. Even Microsoft are betting their house on it, with Windows 8 apps built on HTML and JavaScript.

But what happens when JavaScript Goes Bad on a web page? Here’s the same quick list of errors for a CSS file I wrote about above:

- The server hosting the JS file may be offline

- The file may be temporarily unreadable

- The URL for the file may be wrong

- DNS settings may be incorrect

- The CDN may be down

- The file may be empty

- The file contains something that isn’t JavaScript or a syntax error

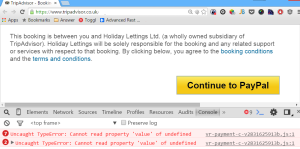

Let’s stop right there and look at the final error. What happens if a browser is parsing JavaScript and finds a syntax error (not quite all errors, but a lot) or something it can’t execute? It dies, that’s what happens:

“JavaScript has a surprisingly simple way of dealing with errors ? it just gives up and fails silently”

Browser JavaScript parsing engines are still pretty forgiving, but *way* less forgiving than HTML and CSS parsers. And different browsers forgive different things. Now, you might think “Just don’t have syntax errors” but the reality is bugs happen. Even something as innocuous as a trailing comma in an array will cause older Internet Explorer to fail, but not other browsers.

So JavaScript, while powerful and cool, is also brittle and can easily break a page. Therefore it *has to be optional*.

Web apps

You might be thinking “Yes, but my site is a Web Application, so I need JavaScript.” OK, but what is a web app exactly? I can’t say it better than Jeremy Keith, so I’ll just link to his article.

This is the crux of progressive enhancement. Here’s the recipe:

- Start with a basic web page that functions with nothing but the HTML, using standard semantic mark-up. Yes, it will require full-page GET or POST requests to perform actions, but we’re not going to stop there – we’re going to enhance the page.

- Add CSS to style the page nicely; go to town with CSS3 animations if you want

- Add JavaScript to enhance the UI and provide all the modern goodies: AJAX, client-side models, client-side validation etc

The benefits are obvious:

- If the JavaScript or CSS files (or both) fail for any reason whatsoever the page still works

- The use of semantic HTML means the page is fully understandable by search engine spiders

- Because everything is rendered in HTML, not built up in JavaScript, it is understandable immediately by assistive devices

- Serving fully-rendered HTML is quicker than building that same HTML client-side

- Built-in support for older – and newer – browsers and devices

The best web developers on the planet all argue that progressive enhancement is the best way to approach web development. I honestly have no idea why anyone would think otherwise. There’s a good article (it’s actually the first chapter of Filament Group’s “Designing With Progressive Enhancement” book) on the case for progressive enhancement here.

Modern JavaScript

There are some people who use juicy headlines (this is called “link-baiting”) which doesn’t help those developers who are trying to promote progressive enhancement, instead causing JavaScript-loving developers to proclaim “you hate JavaScript!”. You know what developers are like: they get hot-headed. It’s much better to try to think clearly and objectively about development and come up with solutions based on real data.

The reality is that most modern JavaScript libraries don’t support progressive enhancement out of the box: AngularJS included. If there were a way to render standard HTML with real links and forms and then enhance that HTML with Angular I would be all over it, but unfortunately I haven’t found anything that explains how to do it yet.

This is something which I’ve been thinking about a lot, and I did a little proof of concept for a basic data-binding system. I wonder if it would be possible to apply the same techniques to Angular.

For me personally I’m a big believer in progressive enhancement, not just for accessibility reasons but for front-end performance as well. I do recognise it will probably add time to development, however the same can be said for Test Driven Development. The goal for progressive enhancement and TDD is the same: a better, more stable foundation for systems.